History of St James' Church

Introduction

This guide is by an ‘interested parishioner’, and makes no claim to be expert analysis. It seeks to describe mainly what can be seen inside the church, as well as offering a reasonable interpretation of the evidence before you, based on background knowledge of churches and church history generally.

St James’ Church sits in the middle of our village. It is an imposing building, and is easily visible from the B1077 which passes through, its slightly out of true east window and the flushwork on the east and north walls giving promise of interesting things to be found inside. It was constructed around the mid-1300s, of flint with some stonework dressings (which are restored), and is set in a modestly sized still open churchyard. It has north and south aisles and chapels, clerestory, and a large nave/ integral chancel. The vestry and ringing chamber above, with west window/door are all part of the tower.

There is a good peal of 6 bells, battlements with the remains of corner figures, and a ‘candlesnuffer spire’. It has an interesting north porch, but also a south entrance (beautiful new door added a couple of years ago) which may have led straight into a baptistery area as there are signs of timber cuttings inside suggesting a partition. There is a priest’s door in the chancel so four still active doors in all, with a fifth now built over, in the Mortimer Chapel and the site of our war memorial. I have recently read that this blocked door led to the actual Mortimer chantry chapel (now gone), with the existing chapel being solely dedicated to the Virgin Mary. I need to look further into this.

Entering via the north door, one is immediately struck by the bright interior, practically all of the stained glass having disappeared during the long stages of the Reformation. That visible now is relatively modern. At this point it is good to remember that all our ancient churches have changed inside in some way as the various re-orderings have taken place in response to different approaches regarding forms of worship, taking them away from their Roman Catholic origins and layouts. Briefly, we know that in the earliest days there would have been few places to sit (if any) in the nave. There may have been benches along the walls for the elderly and infirm (hence the saying ‘gone to the wall’ meaning in reduced circumstances). Permanent stone benches can be seen in some churches. Then the ancient pews or benches would have been installed, to be replaced in their turn by areas of Georgian box pews and the west gallery. The box pews were removed (thankfully not the contemporary gallery) at the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, when there was a major reflooring and reordering of steps and so on, followed by two generations of chairs. Sadly, the pew plinths in the nave and aisles remain, which prevent us having a completely flexible area, though room can be made for tables/extra seating for some of the modern services, fund-raising activities and concerts. There is a servery area, and a lavatory in the vestry.

St James’ mercifully escaped the worst excesses of Victorian restorations, though they without doubt cared for and maintained the church. What you see now is a building that a medieval person might generally recognise once they had got over the shock of the changes to furnishings, flooring, coloured glass, wall paintings and the lack of coloured decoration. Originally the church would once have had a full brightly coloured screen and rood loft in place, and have glowed with colour, gilded statues, stained glass, wall paintings, highlit by flickering candles and lamps. As well as the Reformation, our area was subsequently very ‘Puritan’, and these things combined to produce the defacement of the majority of stone corbels supporting the roof timbers, and very much else besides. We have quite a plain church now, but that in a way leaves it possible to appreciate its spaciousness and relative grandeur for a village that wasn’t large (though that seems to be rapidly changing). There are many echoes of the past - the place is full of clues such as empty notches, slots, and holes, and chunks out of the column bases. Additionally some other precious fragments, generally from the 15th century, remain to tantalise our imaginations as to what our ancestors must have seen then, and observed as changes progressed.

A guide to some items of interest

North Aisle

|

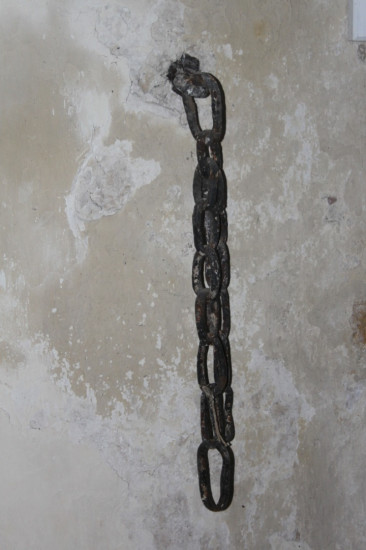

Book Chain Remains of chain, presumed to be a relic from the instruction in 1538 (following Henry VIII’s separation of the English Church from Rome) that all churches should provide a copy of the Bible in English, though it could be later. The Bible was required to be chained to ensure it was always available in that place, and to deter thieves – as plentiful in those days as in these. However, not all ordinary folk could read at that time so once the instructive wall paintings had gone, they had to rely on readings and sermons by others. |

|

|

Rood Stairs Mounting a little wooden step first, the worn stone stairs took you up to the walkway along the loft on top of the 15th century screens. 21st century people would struggle to use this narrow stairway, a testament to improvements in nutrition and development since the 14th century. |

Remains of screens

Screens were once a big feature of every pre-reformation church, dividing the priest’s chancel space from the public nave, and here they also kept the two side chapels as separate areas with their own functions (parclose screens). The surviving dados, which are not all in place, allow us to visualise their original highly coloured and gilded state.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

They were connected to the overhead galleries (notches for the additional supporting timbers can be seen at the top of the columns) by elegantly carved tracery arcading, with statuettes of saints attached in places, and maybe candle sconces along the top for special festivals (which can be seen locally at Rocklands St Peter’s Church when the Gospel could also be read from up there. The nave/chancel section, (and where this may have originally been is a point of conjecture) as well as having an access way between these areas, was surmounted by the rood. This was the large overhead crucifix with its accompanying figures of the Virgin Mary and St John. All churches had been required to have this surmounting rood but though some galleries still exist, every single rood was destroyed during the long reformation process. Anything you see now is a modern revival. Some screens, or parts of screens were preserved in situ. Many churches in Norfolk and elsewhere retain far more of their beautifully painted screens, which may have either been temporarily whitewashed to hide the saints, defaced or in a more sympathetic, maybe remote, religious environment they remain intact and beautiful. But at least we have these fragments. A study of screens is interesting in its own right. Traces of local family insignia may still be seen on them, sometimes on the reverse, though here they were generally obliterated, as the Puritans saw them as emblems of the old order which they wanted to sweep away.

Mortimer Chapel

Originally the chantry chapel of the influential and wealthy Mortimer family, who paid for its construction (and maybe the church too?) as a place for the saying of masses for their souls in perpetuity. Note the blocked door mentioned above, and the statue corbel – the only one to survive intact in this church. This chapel was the original Lady Chapel, and Mary’s statue would have rested on this corbel.

Chancel

Wall Paintings

All around can be seen traces of medieval and later wall paintings which still exist under the grimy centuries of lime wash. Cost precludes their exposure, and anyway they are safer under there for now. Tiny areas of medieval glass with a foliate design can be spotted by the keen-eyed at the top of some of the north chancel windows. Not destroyed with the rest as they were acknowledged as unlikely to put anyone’s soul into peril.

Jacobean Altar

This altar looks as if it may be a modified Jacobean table which, immediately post reformation and in its original form, would have been placed lengthways further down the chancel for the reformed institution of the occasional ‘Lord’s Supper’ which replaced the Mass, stone altars having been banned and destroyed. Later, when altars were allowed again, the local carpenter seems to have moved the original legs so that they were now along the front of the lengthened table, and added new supports to the back. Table became altar. Between the altar and the east wall, under the carpet, is what’s left of the original stone altar top, the mensa. It is broken, shortened and with the width reduced, but still retains some of the original crosses engraved on the surface, with traces of red pigment.

Nearby note the piscina (to wash altar vessels) and the scanty remains of the stone priests' seats (sedilia) next to it. The piscinas drained into the foundations so that the water which had touched consecrated vessels could not be used for witchcraft or more mundane things – and there were no main drains to take it away of course.

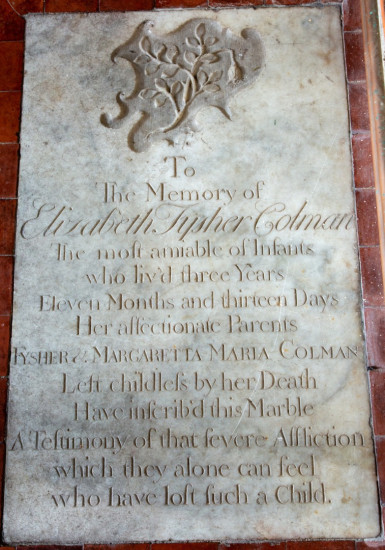

Ledger stones: note the brass thought to be Alice Conyers dated by costume design to around 1500. Other interesting ledger stones, some of which would have carried brasses, and others from early and later times lie around the chancel floor. Well worth a look. A priestly interment is indicated by a chalice surmounted by the Holy Sacrament wafer. Illustrated is one particularly poignant ledger and its associated chancel wall memorial.

8/9***

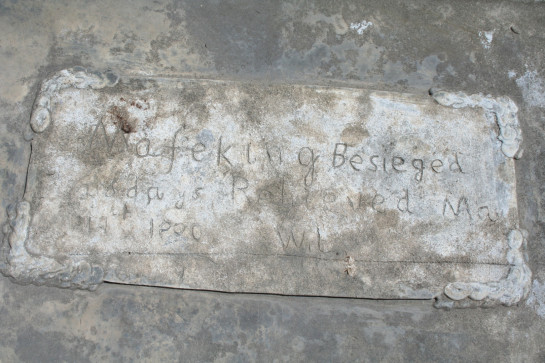

There are other ledgers around the church, all re-laid into the ‘new’ tiles, and probably even more under the pitch that secures the parquet wooden plinths. There is reported to be at least one crypt somewhere. In the servery area can be found in the floor some stones worthy of further thought.

Nave

It is quite common in churches to find that the columns on the north and south aisle vary slightly as here. This could mean there was a change of mason or fashion during construction, or another reason we don’t know. Certainly, it is thought that this church was pretty well built in ‘one go’, aisles and all, give or take a short break. Interestingly, this church was built around the time of the first great plague so maybe there were temporary breaks in construction. Find the base of a north column which carries a mason’s mark.10*** There are traces of lime wash on some of the stonework, and the picture of St Michael in the south aisle clearly indicates that much of the stonework was never meant to be exposed. It was the overlying plaster that carried all the painted pictures and decorations. A careful look around, including on the top clerestory, shows places where the stone was scarred to better enable plaster to stick. The columns tell a more recent additional story. All have been savagely hacked away at the base to enable the installation of post reformation box pews (a plan of which still exists). The whole place, chancel and side chapels, was full of box pews and a few benches, with maybe a monumental pulpit and clerks/readers desk. This reflects the period when all ceremony had been banished and preaching ‘The Word’ was paramount.

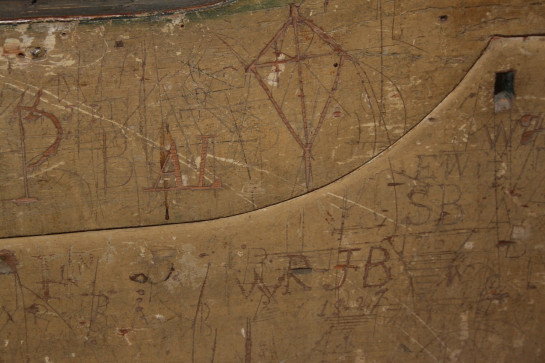

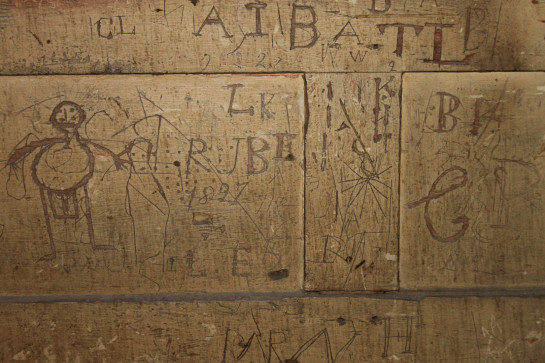

At the west end is the Georgian musicians’ gallery. There was no organ then, so apart from the years when all music in church was banned, local players and singers would squeeze in here. It now almost fulfils its original purpose as it houses the speakers to the electronic organ. On the wood inside the gallery is a lot of historical graffiti which is worth looking at, but beware of the perilous stairway!

Font

This (original) font may have moved around the building a bit in its time, but still has the original lead lining and drain plug, draining into the foundations. The defaced badges may have been family heraldic designs or may have carried emblems of the passion – both of which would explain their destruction. At best the Puritans considered them unwanted decoration. Traces of blue colour remain to tantalise us.

Roof corbels

Many stone roof corbels are further proof of local ‘Puritan’ zeal of the time, evidence of the changes in belief and practice over the centuries and a fear of even the most innocent face encouraging idolatry. Spot the rather (by today’s standards) naughty one…….to the medieval mind this was to spite the devil. It is interesting that was one of the survivors, but then, it isn’t a face …..no idolatry involved.

South Aisle

Chapel

Bloomfield, writing in the 1700s, says that this was originally the guild chapel of St Peter, though now called the Lady Chapel. There are two piscinas (one is under the Lady statue). One was for washing the priest’s hands and the almost adjacent one for washing Mass vessels. They too drained into the consecrated foundations.

Statue Niche

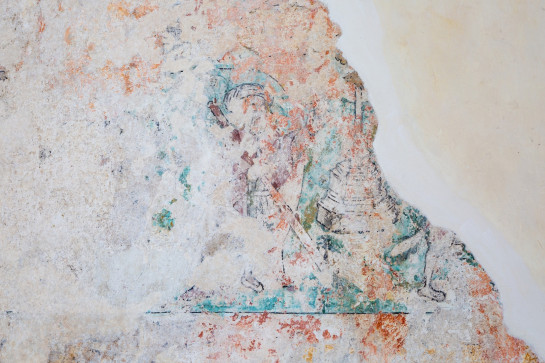

One of the glories of this building, this 15th century painted niche was rediscovered under plaster in the mid-20th century.16*** The original destroyer had thoughtfully (and perhaps with much regret at having to carry out this desecration) walled in a few remaining decorative fragments, which have been restored as far . It would have held a seated statue - possibly brightly coloured and gilded alabaster from the thriving contemporary industry in Nottingham – of Mary and the infant Christ. Or it could have held a Pieta, a depiction of Mary holding the dead Christ in her lap. This representation was very popular at the time the niche was constructed. The reason for the ‘cut out’ on the left hand side is unknown. Holes to take lamps or candle fittings can be seen within the decorated area surrounding the niche. It would have been spectacular in its prime. Sadly, although it was restored in 2012, the colour continues to disappear with the passing years. I have a book which clearly shows far more paintwork on an old photograph.

St Michael Picture

In the window jamb adjacent to the niche can be seen a faint grey image of St Michael weighing souls of the recently departed. 17*** St Michael was deemed to be the first barrier the medieval soul met on its way to heaven. He would weigh the souls, whilst Mary in the adjacent niche, prayed for them. If they passed, they went on to further judgement. If they didn’t even pass that test they were thrown to the demons and consigned to hell. The tail of a demon trying to snatch a soul from the balance scale is just visible. It was all very real to the medieval mind, when life could be hard and short, and life in heaven was by no means guaranteed, though there were ways and means, sometimes involving money ……

Consecration Crosses

Remains from when the bishop consecrated the building in the 1300s. There would have been others.

Wall Painting of St Christopher

In its traditional place opposite the main entrance are the remains of a painting of a turbaned St Christopher at the moment of his conversion. 19*** At this point he was a non-believer (depicted in a medieval non pc way in a turban), and was walking with his friend the devil. They came to a wayside cross and the devil, in the disguise of a dog, made a hasty retreat. A conveniently located local hermit explained why the cross frightened the devil. It is rare to have a picture of this instead of the usual depiction of St Christopher carrying the infant Christ across a river. If the latter existed nearby no trace apparently remains. This was restored in 2012. There may be other traces of paintings in this area, and indeed in other places in the church. This is why it was recommended that the walls be left well alone and explains why we do not have a pristine white interior, but the cracked and time-weary walls you see. The cracks and damage tell their own story in those places where you can make out multiple layers of wash applied over the top of each other as the years progressed following the Reformation.

South Door

Note the new south door.20*** Made by Stephen Hubbard of Norfolk, this beautiful door was completed in 2016 and is a fitting addition to the church. The door now becomes part of the history of St James’s Church and its maker joins the ranks of those craftsmen and visionaries of all disciplines, mostly unknown to us, who helped to make this building what you see today. This door will stand here, darkened with age, when we are long gone, a testimony to 21st century craftsmanship.

In conclusion

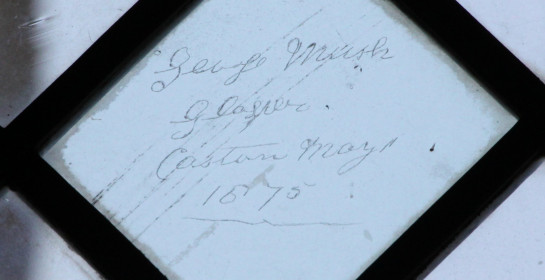

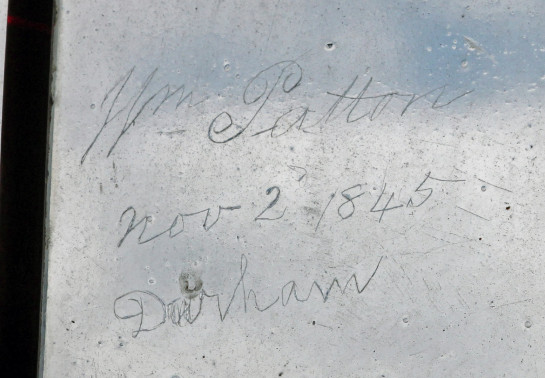

Inside the building there is much more of interest to be seen and thought about, in addition to those mentioned above, e.g. the names of glaziers engraved on various window panes, of which there are several.

Outside, consider the construction of the north porch; note the ‘putlog holes’ 22*** in the outside walls from when the church was constructed, to be found in places such as the tower where you can see the progression as the construction grew upwards; compare the flint flushwork on the north and south sides.

There are other wonderful things but as they are on the roof and inaccessible, and therefore impossible for the visitor to see, you must make do with these photographs out of context.

Not many yards from the church, many human remains have been recently excavated in an extensive burial ground dating back to the later Roman period. It is interesting to speculate whether the church was built here, in an area which had been known for generations as hallowed and respected. Also, was there an earlier church? There is nothing in Domesday (which was fairly normal), and no visible evidence.

We hope that you can enjoy seeing much of the above in person sometime. Like all medieval churches, to anyone with the time to look and listen it can tell you a great story.

Tina Moon 2019

With photographs by kind permission of Steve Moore-Vale

.JPG)